Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

City of Steel. Student  Lasse Branding regularly travels to Bosnia, the land of his ancestors. In centrally located Zenica, he documents the local steel mill’s impact on the town’s people.

Lasse Branding regularly travels to Bosnia, the land of his ancestors. In centrally located Zenica, he documents the local steel mill’s impact on the town’s people.

Because of the industry and its many high-rise buildings, Zenica has the reputation of a grey working-class city. In 1882, under the rule of Austria and Hungary, the narrow-gauge railroad was completed and connected Zenica, which had been isolated until then, with the rest of the world. By train, the city’s inhabitants could now travel to the capital, Sarajevo, 70 km away. Surrounded by hills and fruit trees, there was not more than one village in the central Bosnian province at the beginning of the 19th century until the steel mill “Željezara” was built in Zenica in 1892. Under the five-year plan announced by Josip Broz Tito in 1947, Zenica rapidly developed as a steel and coal centre in the former Yugoslavia, becoming one of the country’s most important exporters. The plant was enormously expanded and rebuilt into one of the largest in Europe. People from all over Yugoslavia came to Zenica to work in the factory.

After the breakup of Yugoslavia, Lakshmi Mittal, one of the wealthiest men in the world, bought up most of the Bosnian steel industry with his company Arcelor Mittal in 2004. The deal was generally welcomed in Zenica – many saw it as a chance for work and a return to normalcy in a city devastated by war and hardship. Arcelor Mittal kept the steel mill in operation, but a lack of investment in new jobs and no environmental protection upgrades caused growing resentment among the population. The ambivalence of curse and blessing highlights the relationship between factory and city. On the one hand, the factory made the city what it once was, but on the other hand, the factory also brought a lot of suffering to the residents of Zenica. Today, the factory’s decline also means the city’s fall.

Lasse Branding’s work describes the state of a post-industrial working-class city of the former Yugoslavia and addresses the question of what a city built based on production growth looks like when growth shrinks. The socialist labour system ensured a high identification of the workers with the factory, which they once described as the “cradle of the proletariat.” Today, only a few residents still identify with what was once the largest ironworks in Europe. And yet, the inseparable history between the city and the factory remains and is looked back on wistfully.

In 1892, one of the largest steelworks in Europe, “Zeljezara”, was built in the small village of Zenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina under Austro-Hungarian rule. Today, the steelworks are known mainly for their enormous air pollution and the symbolism of Yugoslavia’s industrial decline.

Serif Sisic lives in Tetovo, a suburb of Zenica that borders directly on the steelworks. Sisic worked for 31 years as a manoeuvrer, first at the state-owned company “Zeljezara” in Yugoslavia and later, after the privatisation of the steel plant, at Arcelor Mittal. Like many of his neighbours and former factory workers, Sisic also fell ill with throat cancer and had to leave his job for health reasons. He says that the factory’s exhaust fumes discolour the snow in winter, and the fruit becomes dusty in summer.

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

A railway employee checks incoming wagons—these transport coke from other parts of Bosnia to fire the blast furnaces.

The play “Moja Fabrika”, in English “My Factory”, is performed in the theatre. The play is about the origin of Zenica, as a small village, through the glorious times in Yugoslavia, to the decay of the factory and the city. The play was written by the author Selvedin Avdić from Zenica and is performed among others by former steel plant workers “Zeljezara”.

The steel beams are counted per heating period in the mill’s rolling mill. In 1987, the most productive year, the steel mill had a production volume of 1.87 million tons of steel per year and employed over 24,000 workers. Today, global steel giant Arcelor Mittal keeps the plant at a production minimum, and just over 2,000 workers are still employed. Many parts of what was once Europe’s largest steel mill are left to decay.

Zenica, Bosnien und Herzegowina, 2021 – 2022

Zenica, Bosnien und Herzegowina, 2021 – 2022

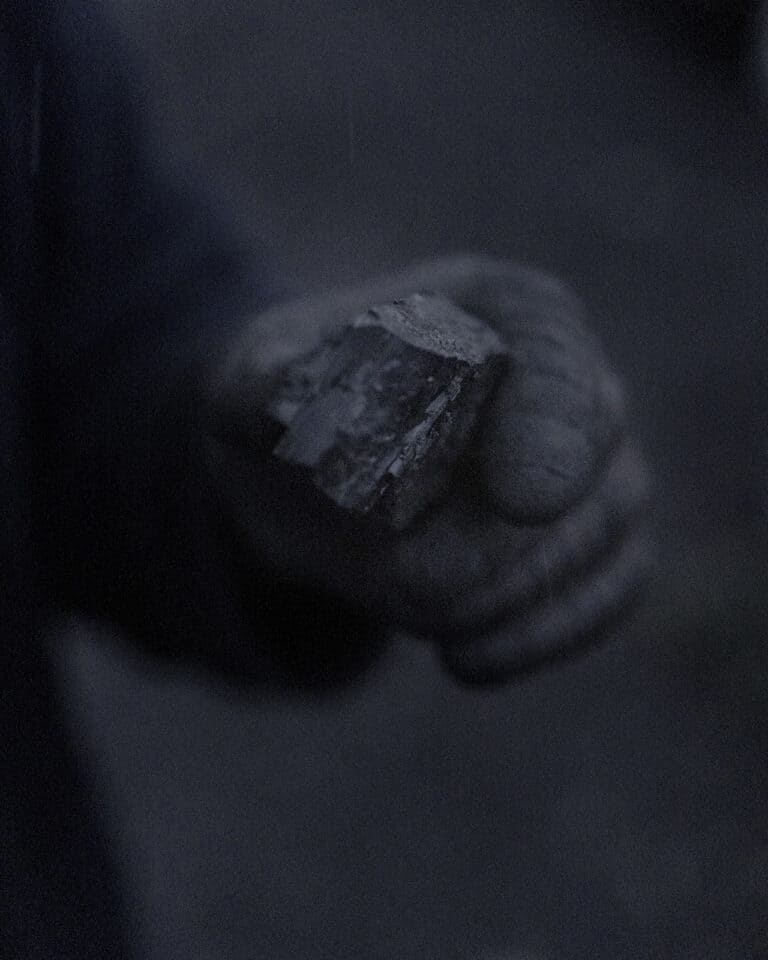

One of the country’s largest coal deposits lies beneath the city. There are discussions about closing the mine because the largest customer of the steel mill has switched to coke and imports it from other parts of the country to heat the blast furnaces.

Samir Lemes checks the factory’s construction waste for contamination and pollution at a landfill site. Meter-high mounds of industrial waste pile up above the village of Tetovo. Samir Lemes joined the environmental group in 2009 and is now the president of the local environmental organization. The year before Lemes joined, his father had died and he was concerned about the impact of pollution on his two children. “Every winter we cough, fall ill with the flu and similar health problems for which I blame pollution.”

Landfills and scrapyards have sprung up around the steel mill site to recycle waste material from the mill.

A Muslim cemetery in front of the steel mill in winter.

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

Ballet dancers of the “ARS Centar Zenica” during a rehearsal of their new piece “War Memorial”, which deals with the memories and traumas of the Bosnian war of 1992-1995.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has the fifth-highest incidence of deaths from air pollution globally, and rates of lung disease are among the highest in the world. As a result, many people in Zenica suffer from respiratory problems and cancer. Meanwhile, town residents have formatted against the factory’s rudimentary maintenance and are demanding environmental improvements.

The ultras of the local soccer club “Cèlik Zenica” call themselves “Robijaši”, in English “Prisoners”, and were named after the largest penal institution in Bosnia, which is also located in Zenica. The term was also translated in the former Yugoslavia as “the strictest”.

Two supporters of the local soccer club “Cèlik Zenica” (“Steel Zenica”). In Yugoslavia, the club was one of the most successful in the country. Today, after forced relegation to the amateur league, the club again plays in the second division and hopes to be promoted.

A covered market stall in the centre of Zenica.

View from the roof terrace of the “Hotel International”. The hotel was opened in 1978 to accommodate high-ranking state and business delegations, and they came to Yugoslavia to conclude agreements with the ironworks. When it was opened, it was luxuriously furnished and fully air-conditioned, had a sauna, several restaurants, and numerous works of art on the walls. Today, the hotel is insolvent and hopes for new investors.

Verdad Càtovic worked for 25 years at the “Hotel International” reception, run by the “Zeljezara” steelworks. Càtovic has set up his tiny room with a TV and heating in the lobby, where he occasionally stays overnight. He hopes that the hotel will find new investors and that numerous guests will revive the ageing building. Until then, Càtovic is guarding the hotel and protecting it from decay.

The steelworks built many green areas in the city with recreational facilities for the factory workers.

Samir, Nadja and Ilhana enjoy their spare time in the city’s surrounding hills.

Residents of the city gather at the Yugoslav partisan memorial on the mountain “Smetovi” on the weekend to escape the stuffy air in the valley.

During a blessing, residents gather in the Orthodox Church “Crkva Rodenja Presvete Bogorodice”. Before the war, an estimated 22,552 Bosnian Serbs lived in Zenica. Today, only about 5,000 live in the city.

A resident of Zenica walks his Belgian shepherd dogs along the city’s railroad tracks. Once a year, he goes to the Netherlands and sells the trained dogs at auctions.

Harum is studying civil engineering in Zenica. In the summer months, he – like many of his fellow students – works in Germany for the post office and delivers parcels. The German post office cooperates with Bosnian universities to get temporary workers during summer. Harum’s father also worked in the steel factory until he became too ill and had to take early retirement. After graduation, Harum would like to find a job in Zenica and get married.

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021 – 2022

During the fasting month of Ramadan, numerous city residents hike together through the surrounding mountains until they break their fast after sunset. The initiator of the hikes, Afan Abazovic, calls the action “Iftar Hiking”. In Zenica, an estimated 90% of the population are Muslims.

At dusk, the air pollution in Zenica becomes particularly evident.

Your contact partners will be happy to assist you with your personal concerns. However, due to the large number of enquiries, we ask you to first check our FAQ to see if your question may already have been answered.

Dean of Studies, Design and Media department

Programme representative

Application and admission procedure

Hochschule Hannover

Faculty III – Media, Information and Design

Expo Plaza 2

D-30539 Hanover