Between stony fronts. Since 2017,  Daniel Chatard has been photographing the conflict surrounding coal mining in North Rhine-Westphalia in his work “No Man’s Land”.

Daniel Chatard has been photographing the conflict surrounding coal mining in North Rhine-Westphalia in his work “No Man’s Land”.

Daniel is stunned when his friend tells him the story of threatened villages to be forcibly relocated for lignite mining in Germany. Curious, he decides to travel to the Rhineland and investigate further. There, he meets activists who live in tree houses as part of their campaign against the logging of Hambach Forest.

Contact with them is difficult at first. The activists are suspicious of the media and only want to be photographed hooded. But Daniel doesn’t let up: He keeps driving to the Rhineland, spending the night in the forest. He even helps build tree houses. He soon succeeds in winning the trust of the activists. They also show him how to climb into the tree houses: You secure yourself to two loops. Like a caterpillar, you then pull yourself up, piece by piece.

Meanwhile, Daniel is also working on a book dummy. For this purpose, he is on the road again in the Rhineland to have affected people from the villages write down their thoughts. For him, this creates an exciting dialogue: The meaning of his images is renegotiated. These thoughts and quotes will be published at the end with his photographs.

Daniel Chatard now lives in the Netherlands. His work has been published in ZEIT, National Geographic, and the Washington Post, among others. The exchange during his studies meant a lot to him, as did the solidarity of his fellow students: “Even if you were stuck on something, someone could always explain it to you,” says the photographer. “No Man’s Land” was nominated for the Leica Oskar Barnack Award in 2018 and exhibited at the FOTODOKS Festival in Munich the following year.

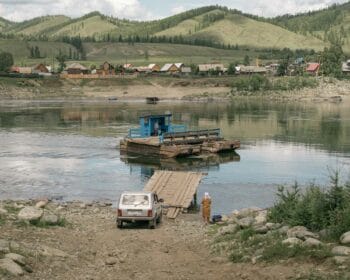

Manheim-neu, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Manheim-neu, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

In February 2020, residents of the resettlement site “Manheim-neu” wait for the passing carnival procession.

Bedburg, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Bedburg, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Demonstrators of the action alliance “Ende Gelände” evade a police blockade during an action in August 2017 and climb a hill back onto the road.

Erkelenz, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Erkelenz, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

In November 2021, the new German government announces its intention to save Keyenberg and four other villages threatened by the Garzweiler II opencast lignite mine. About 80 per cent of the inhabitants had already been relocated by this time.

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Activists carry a tree trunk through the forest to build a tree house with it.

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

“Robin” inhabited the Hambach Forest for several months. Almost no one here knows the others’ real names, so aliases a.

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Meanwhile, the Hambach Forest is occupied by dozens of tree houses, the highest at about 25 meters. Almost all tree houses can only be reached by climbing, making them difficult to clear.

You must learn to climb if you want to get into the tree houses. You secure yourself with two loops. Like a caterpillar, you then pull yourself up, piece by piece.

Erkelenz, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Erkelenz, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

In January 2021, the alliance “Kirche(n) im Dorf lassen” organised a blessing of the houses still standing in Lützerath. A few months later, RWE will demolish some of them.

Immerath, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Immerath, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

To expand the Garzweiler open pit mine, the parish church of St. Lambertus, popularly known as “Immerather Dom”, will be demolished in January 2018.

Erkelenz, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Erkelenz, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Marita Dresen is involved in the alliance “Alle Dörfer bleiben” (All Villages Remain) to preserve the villages threatened by the Garzweiler II open pit mine, whose resettlement began in 2016.

Garzweiler open pit mine, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Garzweiler open pit mine, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Several hundred activists entered the Hambach open pit mine during an action by the “Ende Gelände” action alliance in November 2017.

Bedburg, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Bedburg, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Police officers carry away a demonstrator after they have surrounded him with hundreds of others in a field in front of the coal railroad tracks. All demonstrators are taken away in buses.

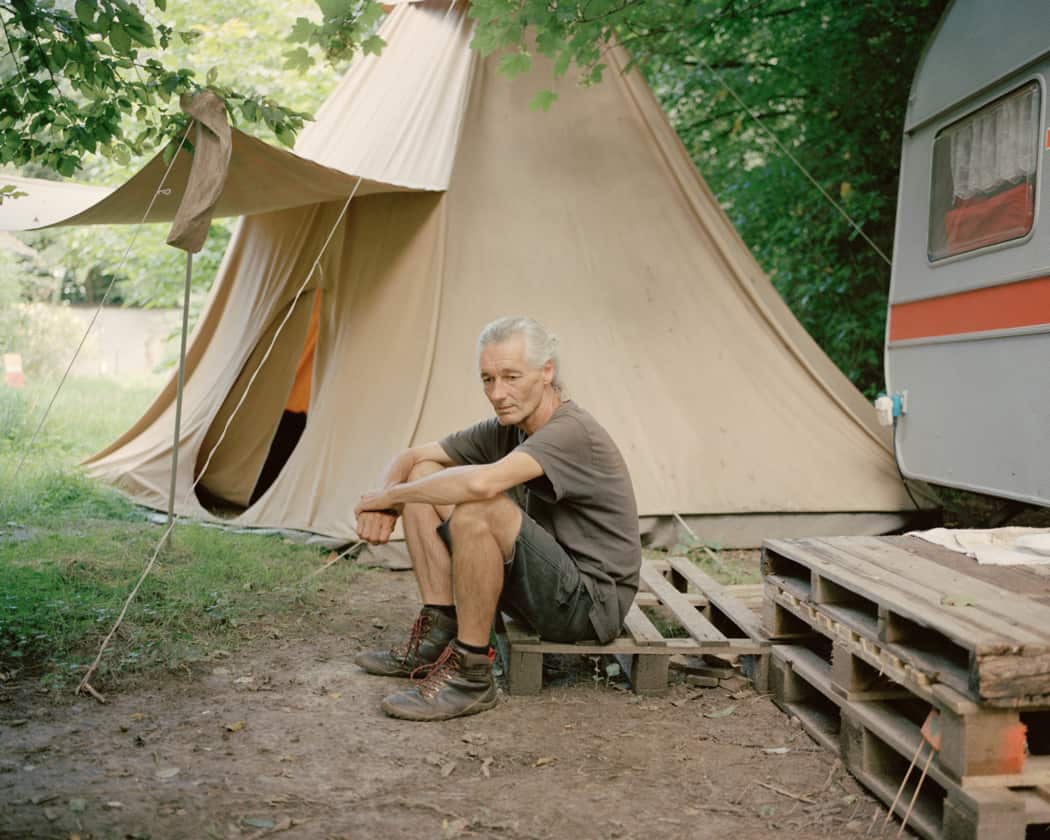

Lützerath, Erkelenz © Daniel Chatard

Lützerath, Erkelenz © Daniel Chatard

Fred and many other local activists are fighting to preserve the village of Lützerath.

Hochneukirch, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

Hochneukirch, North Rhine-Westphalia © Daniel Chatard

In the Otzenrath House Museum, Inge Broska, a former village resident, exhibits found objects left behind during the village’s resettlement.

Manheim-neu, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Manheim-neu, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

The Manheim-neu resettlement site is located a few kilometres away from Mannheim. The groundbreaking ceremony took place in 2011; today, about 1,000 people live there.

Keyenberg, Erkelenz © Daniel Chatard

Keyenberg, Erkelenz © Daniel Chatard

Activists Robin and Jillie live in the tree houses even in sub-zero temperatures.

Hambach open pit mine, Elsdorf © Daniel Chatard

Hambach open pit mine, Elsdorf © Daniel Chatard

The Hambach lignite mine is 400 meters deep, and a residual lake will be created from it one day. Filling the lake with water from the Rhine is expected to take several decades. However, environmental groups doubt the feasibility of the project.

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

Hambacher Forst, Kerpen © Daniel Chatard

“Clumsy” was already present at the first forest occupation in 2012 and has lived in Hambacher Forst almost continuously for over five years.

Hambach Forest, Merzenich © Daniel Chatard

Hambach Forest, Merzenich © Daniel Chatard

Police and SEK officers cleared the tree house settlement “Lorien” in Hambach Forest during the evictions in September 2018.

Your contact partners will be happy to assist you with your personal concerns. However, due to the large number of enquiries, we ask you to first check our FAQ to see if your question may already have been answered.

Dean of Studies, Design and Media department

Programme representative

Application and admission procedure

Hochschule Hannover

Faculty III – Media, Information and Design

Expo Plaza 2

D-30539 Hanover